Published: 1 September 2016

Publications

Beta-lactam Antibiotics and Cross-reactivity

Prescriber Update 37(3): 44

September 2016

Allergy to Beta-lactam Antibiotics

Patients commonly report an allergy to penicillin, however reaction details are often vague and many patients may be incorrectly labelled 'penicillin allergic'1,2.

Careful individual risk-benefit assessment is essential when considering the use of a beta-lactam antibiotic, taking into consideration details of the history of the prior reaction and allergy test results3,4.

In addition, consideration should be given to the structure of the beta-lactam antibiotic that was responsible for the reaction. Cross-reactivity occurs between beta-lactams with a closely related structure and affects antibiotic choice.

Beta-lactam Antibiotic Structure and Degradation Pattern

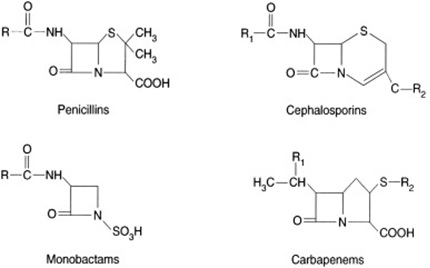

The basic structure of all beta-lactam antibiotics consists of a four-membered beta-lactam ring (Figure 1). In addition to the four-membered beta-lactam ring;

- penicillins have a thiazolidine ring and a single side-chain that differs for each type of penicillin

- cephalosporins have a dihydrothiazine ring and two side chains instead of one

- carbapenems have a slightly different thiazolidine ring structure to penicillin

- aztreonam, a monobactam, has a beta-lactam ring with no adjacent ring.

The beta-lactam ring, the thiazolidine/dihydrothiazine ring and the side-chains are all potentially immunogenic4,5.

Despite their similar structure, penicillins and cephalosporins differ in their degradation pattern. Penicillins break down to form the stable penicilloyl moiety and a range of reactive intermediates. These derivatives have the potential to elicit an immune response4,6. In contrast, the degradation of cephalosporins involves the rapid fragmentation of the structural rings and the degradation products are less immunogenic.

Figure 1: Basic chemical structures of beta-lactam antibiotics showing differences in ring structure and number of side chains (R)6

Cross-reactivity between Beta-lactams

Individuals with an allergy to one beta-lactam antibiotic may react to other structurally similar beta-lactams. Cross-reactivity between penicillin and first- and early (pre-1980) second-generation cephalosporins has been reported to occur in up to 10% of penicillin allergic patients. However, older studies may have overestimated the degree of cross-reactivity as the early cephalosporins contained traces of penicillin4,7. Cross-reactivity between penicillin and third-generation cephalosporins occurs in 2% to 3% of penicillin-allergic patients4,5,8,9. The degree of cross-reactivity may be much higher for beta-lactams with similar or identical side-chains4,5.

Clinical cross-reactivity among cephalosporins mainly relates to the side chains4. However, it should be noted that cephalosporins cause immune-mediated reactions in 1% to 3% of patients even in the absence of a history of penicillin allergy. Therefore, administration of a cephalosporin with different side-chains may still result in an allergic response due to co-existing sensitivities4,5,10.

Allergy Testing to Beta-lactam Antibiotics

If a patient has a convincing history of an immediate hypersensitivity reaction or a severe cutaneous adverse reaction to a specific antibiotic, allergy testing is not required for confirmation and the antibiotic concerned should be avoided2. Allergy testing is mainly limited to immediate, IgE-mediated hypersensitivity3.

A blood test for specific IgE to penicillins is available, but does not include all antigenic determinants. A positive test result is highly predictive of penicillin allergy, but a negative result does not adequately exclude penicillin allergy4,11.

Skin testing for allergy to beta-lactams is a specialist procedure and is only offered at certain hospitals2. Approximately one third of patients with a true penicillin allergy have a negative skin test. Therefore, a negative skin test does not adequately exclude allergy4.

If a patient reacts to a specific cephalosporin, skin testing to another cephalosporin with a different side chain may be considered. If skin testing is negative, graded oral challenge with the alternative cephalosporin, under specialist supervision, may be considered4.

Further information on beta-lactam allergy testing in New Zealand can be found on the Best Practice Advocacy Centre (BPAC) website (www.bpac.org.nz/bpj/2015/june/allergy.aspx).

Further information on the management of patients with beta-lactam antibiotic allergies, including tables of beta-lactam antibiotics that share similar or identical side chains, can be found in the guidance prepared by The Standards of Care Committee of the British Society for Allergy and Clinical Immunology (BSACI)8.

References

- Macy E. 2014. Penicillin and beta-lactam allergy: epidemiology and diagnosis. Current Allergy and Asthma Reports 14(11): 476.

- Best Practice Advocacy Centre (BPAC). 2015. When is an allergy to an antibiotic really an allergy? Best Practice Journal 2015(68): 22.

- Australasian Society of Clinical Immunology and Allergy. 2014. Antibiotic Allergy Clinical Update. URL: www.allergy.org.au/images/stories/hp/info/ASCIA_HP_Clinical_Update_Antibiotic_Allergy_2014.pdf (accessed 21 July 2016).

- Mirakian R, Leech SC, Krishna MT, et al. 2015. Management of allergy to penicillins and other beta-lactams. Clinical & Experimental Allergy: Journal of the British Society for Allergy and Clinical Immunology 45(2): 300-327.

- Romano A, Gaeta F, Arribas Poves MF, et al. 2016. Cross-Reactivity among Beta-Lactams. Current Allergy and Asthma Reports 16(3): 24.

- Khan DA, Solensky R. 2010. Drug allergy. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 125(2 Suppl 2): S126-137.

- Pichichero ME. 2005. A review of evidence supporting the American Academy of Pediatrics recommendation for prescribing cephalosporin antibiotics for penicillin-allergic patients. Pediatrics 115(4): 1048-1057.

- Madaan A, Li JT. 2004. Cephalosporin allergy. Immunology and Allergy Clinics of North America 24(3): 463-476, vi-vii.

- Pichichero ME. 2007. Use of selected cephalosporins in penicillin-allergic patients: a paradigm shift. Diagnostic Microbiology and Infectious Disease 57(3 Suppl): 13S-18S.

- Pichichero ME, Zagursky R. 2014. Penicillin and cephalosporin allergy. Annals of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology 112(5): 404-412.

- Joint Task Force on Practice Parameters. 2010. Drug Allergy: An Updated Practice Parameter. Annals of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology 105: 259-293.e278.