Published: 2 September 2015

Publications

Medicines and Hyperkalaemia

Prescriber Update 36(3): 37–39

September 2015

Background

Potassium is an important electrolyte required for physiological functioning. A slight change in concentration can have a significant impact clinically2. Hyperkalaemia is generally defined as a serum potassium concentration greater than 5.0 mmol/L3.

It is widely recognised that cardiac complications, including sudden death, are associated with hyperkalaemia making prevention of hyperkalaemia a priority4.

Medicines have been considered as a primary or contributing cause of hyperkalaemia in 35% to 75% of hospitalised patients5. Potassium increasing drug-drug interactions (DDIs) are also common, occurring in up to 10% of hospitalised patients1.

Symptoms

Hyperkalaemia is often asymptomatic and discovered on routine laboratory tests. Severe hyperkalaemia (potassium >6.5 mmol/L) is life-threatening3,6. Symptoms are predominantly cardiac or muscular related and include generalised weakness, paralysis, and cardiac arrhythmia3,6. Cardiac arrhythmias are the clinically most important symptom as these may lead to (sudden) death2. Thus hyperkalaemia is associated with increased mortality7.

Medicines that Increase Serum Potassium

Medicines known to increase serum potassium are shown in Table 1. Medicines affecting the renin-angiotensin system are the most common cause of hyperkalaemia6,8.

Table 1: Medicines known to increase serum potassium levels8

| Mechanism | Medicine Type | Medicines |

|---|---|---|

| Reduction of potassium renal excretion due to hypoaldosteronism | Aldosterone antagonists | Spironolactone, canrenoate potassium, eplerenone, drospirenone |

| Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors | Captopril, enalapril, lisinopril | |

| Angiotensin II receptor antagonists | Candesartan, losartan | |

| Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs | Ibuprofen, naproxen, diclofenac, meloxicam | |

| Heparins | Enoxaparin sodium | |

| Immunosuppressive drugs | Cyclosporin, tacrolimus | |

| Reduction of potassium passive renal excretion | Potassium-sparing diuretics other than aldosterone antagonists | Amiloride, triamterene |

| Anti-infective drugs | Trimethoprim, pentamidine | |

| Reduction of potassium cellular transport | Beta-blockers | Propranolol, atenolol, metoprolol, bisoprolol |

| Cardiac glycosides | Digoxin | |

| Mood stabiliser | Lithium | |

| Excess of potassium supply | Potassium salts | Potassium chloride |

| Unknown mechanism | Epoetins | Epoetin alfa, epoetin beta |

Important Drug Interactions

Potassium-increasing DDIs may induce hyperkalaemia and hence life-threatening cardiac arrhythmias1. The risk for hyperkalaemia is increased with the number of concurrently administered potassium-increasing medicines1.

Care needs to be taken when adding a potassium increasing medicine to a patient’s treatment regimen which already includes a potassium increasing medicine. This is most likely to be overlooked when the patient requires short-term treatment with a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) or anti-infective such as co-trimoxazole (trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole).

Recent research has shown an increased risk of sudden death in patients taking spironolactone, angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors or angiotensin receptor antagonists who were also treated with co-trimoxazole for an infection5,9.

Non-medicinal Causes

Other factors may contribute to the risk of a patient developing hyperkalaemia and include6–8:

- increasing age

- dehydration

- renal disease

- hypoaldosteronism

- metabolic acidosis

- diabetes mellitus/insulin deficiency

- an increased potassium supply.

Management

Patients at risk of developing hyperkalaemia should have their serum potassium levels frequently monitored.

When potassium levels start to increase or in mild hyperkalaemia, the potassium-increasing medicine should be reduced and dietary potassium restricted. If this is not effective the medicine may need to be withdrawn6. In patients requiring diuretics, loop or thiazide diuretics should be used6. However, these may have reduced efficacy in patients with underlying kidney failure.

Patients who develop severe hyperkalaemia require immediate hospital attention.

Early measurement of potassium levels, cautious dosing (giving consideration to potassium-increasing medicines), close monitoring of a patient’s electrolyte levels and avoidance of other drugs that cause hyperkalaemia is recommended to reduce the risk of hyperkalaemia9.

New Zealand Cases

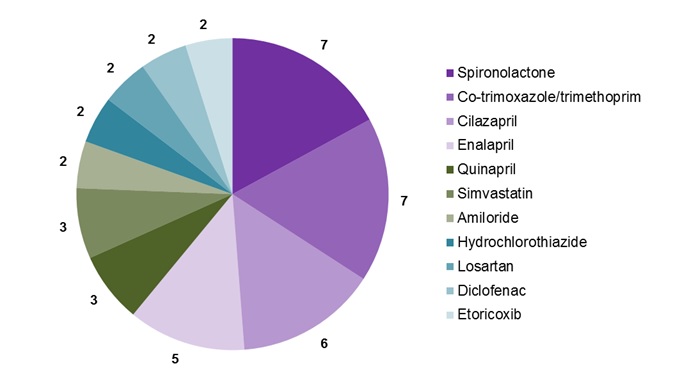

The Centre for Adverse Reactions Monitoring (CARM) has received 60 reports of hyperkalaemia (Figure 1). These 60 reports involved 79 suspect medicines as two or more suspect medicines were described in some reports.

ACE inhibitors and aldosterone antagonists accounted for 25% and 9% of the suspect medicines, respectively. This is consistent with hyperkalaemia causing medicines reported in the literature.

Figure 1: Medicines associated with hyperkalaemia that have been reported to CARM more than once.

The suspect medicine was withdrawn in 40 of the 60 reports and in 33 of those 40 reports a definite improvement of hyperkalaemia was reported.

Healthcare professionals are encouraged to report any adverse events to medicines, including hyperkalaemia, to CARM. Reports may be submitted on paper or electronically (https://nzphvc.otago.ac.nz/).

References

- Eschmann E, Beeler PE, Kaplan V, et al. 2014. Patient- and physician-related risk factors for hyperkalaemia in potassium-increasing drug-drug interactions. European Journal Clinical Pharmacology 70: 215–223.

- Karmacharya P, Poudel DR, Pathak R, et al. 2015. Acute hyperkalemia leading to flaccid paralysis: a review of hyperkalemic manifestations. Journal of Community Hospital Internal Medicine Perspectives 5: 27993.

- Rastergar A, Soleimani M. 2001. Hypokalaemia and Hyperkalaemia. Postgraduate Medical Journal 77: 759–764.

- Ponce SP, Jennings AE, Madias NE, et al. 1985. Drug-induced hyperkalemia. Medicine (Baltimore) 64: 357–370.

- Perazella MA. 2000. Drug-induced hyperkalemia: old culprits and new offenders. American Journal Medicine 109: 307–314.

- Ben Salem C, Badreddine A, Fathallah N, et al. 2014. Drug-induced hyperkalemia. Drug Safety 37: 677–692.

- Henz S, Maeder MT, Huber S, et al. 2008. Influence of drugs and comorbidity on serum potassium in 15,000 consecutive hospital admissions. Nephrology Dialysis Transplant 23: 3939–3945.

- Noize P, Bagheri H, Durrieu G, et al. 2011. Life-threatening drug-associated hyperkalemia: a retrospective study from laboratory signals. Pharmacoepidemiology Drug Safety 20: 747–753.

- Antoniou T, Hollands S, Macdonald EM, et al. 2015. Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole and risk of sudden death among patients taking spironolactone. Canadian Medical Association Journal 187: E138–143.